Two articles addressing the historical complexities and psychological compromises of Asian American life in the United States

“Being Asian American has always been a bewildering and complicated experience. You move to a new country and think you’ll be treated like an American, but what you really want is to be treated like you’re white, which isn’t possible.

There is a common Chinese saying of 吃苦 (chīkǔ). It translates literally to “eat bitterness,” to swallow our pain and suffering and endure it. We persevere and we don’t complain, and it is seen as a virtue: Work hard for things that people can’t take away from you. In a study of ethnically diverse cancer patients, they found that Asian Americans reported the lowest pain scores. My mom would not have seen the terrifying incident with our old neighbor as something to tell us about. Sharing it would have meant she was complaining. He used words. He didn’t cause her physical harm. He didn’t even use a racial slur. So, maybe it really wasn’t that bad.

...

The damaging model-minority myth suggests that Asians actually have it pretty good in this country, especially compared to everyone else, and propels a perception of universal success (in reality, Asians have the largest income gap with one of the highest poverty rates). It also implies that with higher education and hard work, you can chīkǔ racism. I’ve been shamefully ambiguous as to how prejudiced white America is to Asian Americans, giving white supremacy the “benefit of the doubt” it did not deserve. I’ve been constantly made to feel like I should be grateful for what I have, but what I really have is an uneasy, panicky feeling that I should have spoken up for more and sooner.”

via The Cut

“And here we come to the heart of the complexity of “speaking up” for Asian-Americans. Thanks to the “Model Minority” myth — popularized in 1966 by the sociologist William Petersen and later used as a direct counterpoint to the “welfare queen” stereotype applied to Black Americans — Asian-Americans have long been used by mainstream white culture to shame and drive a wedge against other minority groups.

...

These past few weeks, it seems as if Americans have opened to a kind of knowing. As I saw these recent incidents of anti-Asian violence unfold in the news, I felt a profound sense of grief. But I also experienced something akin to relief. Maybe, I thought, now people will start to respond to anti-Asian violence with the same urgency they apply to other kinds of racism.

But then I started to feel a familiar queasiness in the pit of my stomach. Is this indeed what it takes? A political imagination (or, really, lack thereof) that predicates recognition on the price of visible harm?”

5 Notes for the "Side Hustle"

1. Screen shot taken from an email newsletter

“Wondering how to start a side hustle on Instagram? Spoiler alert: it takes a bit of hard work.

However, with the right strategy, you can build a thriving community and drive those all-important sales, while still holding down a full-time job.”

via Later

2. Roy Wood, Jr on the “side hustle”

3. Squarespace Superbowl Ad

4. “Comments are turned off”

5. “Learn More”

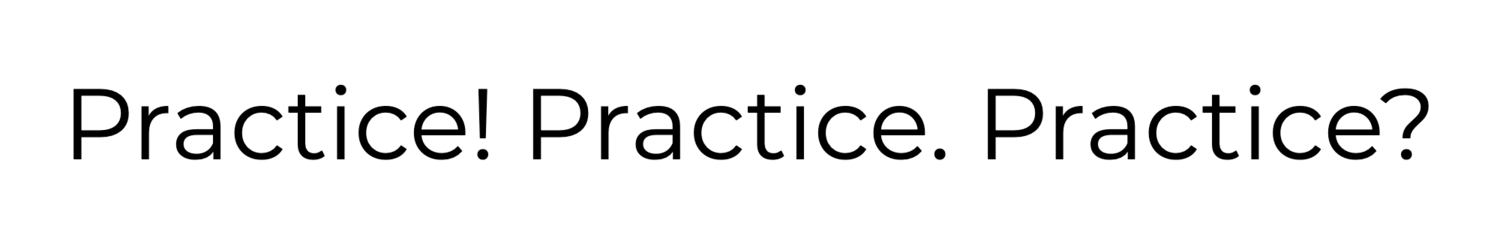

“To accomplish this, 9to5 appealed to women workers through tactics full of humor and personal connection. They held mock contests, such as one for the “pettiest office task,” once awarded to a secretary who had to sew up the crotch of her boss’s pants while he was still wearing them. They made up songs and funny slogans; one flyer featured an illustration of a stick of dynamite struck in a high-heel shoe and read “women in insurance: an explosive situation.” They “pilloried these bosses by name,” as Nussbaum puts it. “We would take the press with us to go announce who the bad boss was that year.”

“We did things that were fun because we wanted to have fun,” Nussbaum says. “It wasn’t a tactic so much as we wanted to build the kind of organization we would want to join.””

via Jacobin

"Walis tambo" and the Capitol Insurrection

“While Asian-American voters delivered for Biden in battleground states, one in three Asian-Americans across the country supported Trump, an analysis by the New York Times showed. ”

“While others laughed, the broom man was generally slammed on social media in the Philippines, as people expressed disgust at the support for Trump and the mob.”

Andi Schmied's "Private Views: A High-Rise Panorama of Manhattan"

Did you dress up?

Yes, of course! I spent my entire budget I got for this arts residency on clothes and bags and manicures and makeup. But it wasn’t like anything very extreme — I was opting for sophisticated lady, somehow …

Understated but expensive.

Exactly — no brands. But after a while I realized that it absolutely doesn’t matter what I wear: From their point of view, you’ve passed the access, and you can do anything — anything is believable. For example, all the pictures were taken with a film camera, which is [gestures broadly] this big. I’d just ask, “Can I take some pictures for my husband?” which is a very obvious and normal thing to do. There were a few agents who noticed that it was a film camera, not a digital camera, and those who noticed asked, “Oh, wow, is it film?” And I’d always say something like, “Oh, my grandfather gave it to me — to record all the special moments in my life.” And they’d just put me in this box of “artsy billionaire,” and would start to talk to me about MoMA’s latest collection. So anything goes.

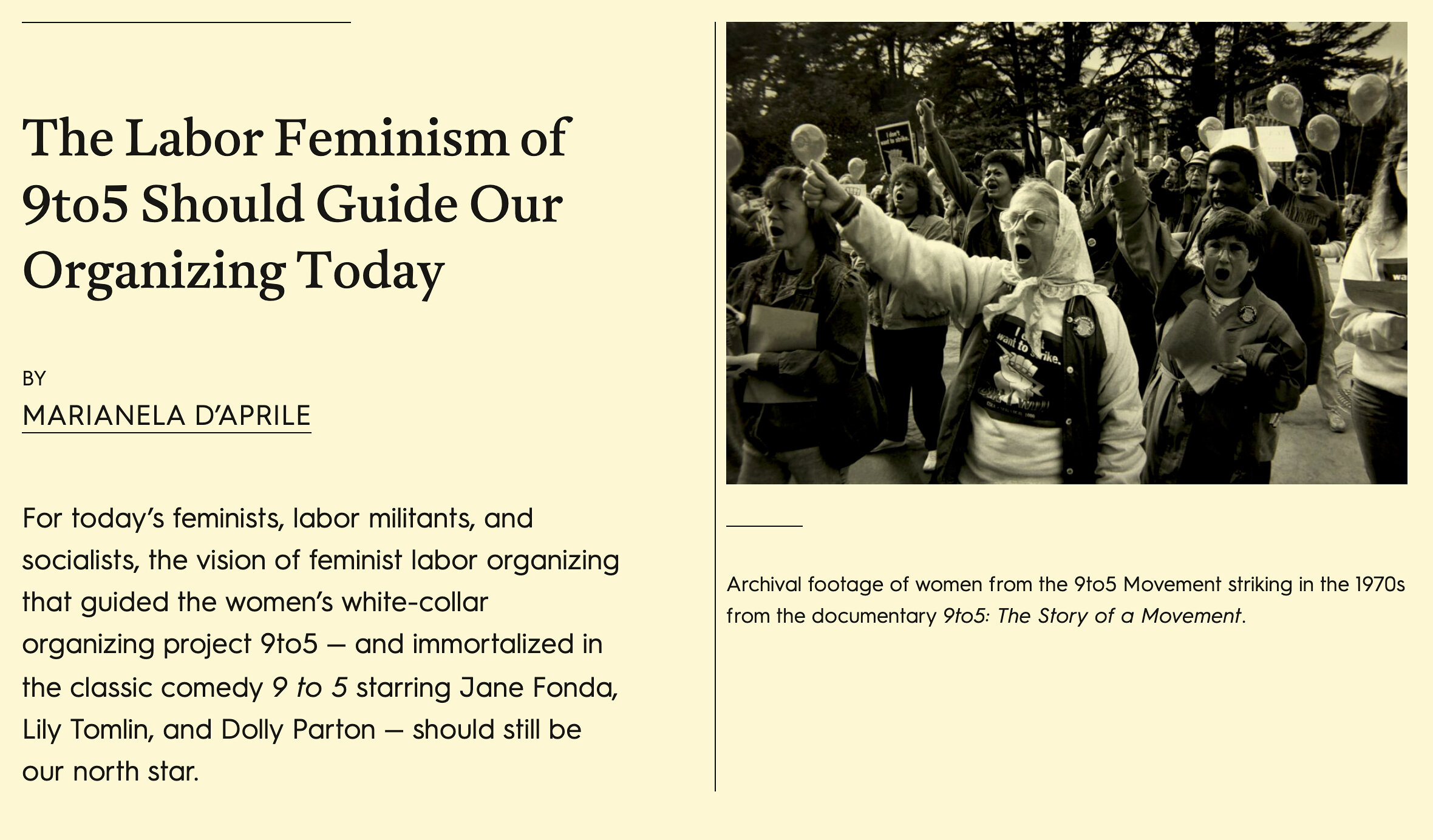

Christine Sun Kim: 2019 Whitney Biennial

Took these four pictures when I was in NYC last year and caught the 2019 Whitney Biennial (I think there were six total prints, however). These works by Christine Sun Kim were new to me, and my favorite encounter from the exhibition. Below is a short interview with the artist and her work and processes.

Article via The New York Times Magazine

Artist Website: Christine Sun Kim

Frederick Douglass, photography, and the image of dignity

“He wrote essays on the photograph and its majesty, posed for hundreds of different portraits, many of them endlessly copied and distributed around the United States. He was a theorist of the technology and a student of its social impact, one of the first to consider the fixed image as a public relations instrument. Indeed, the determined abolitionist believed fervently that he could represent the dignity of his race, inspiring others, and expanding the visual vocabulary of mass culture. ”

via The New Republic

Additional Essays

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay on imperialism, history, and "Unlearning the Origins of Photography"

The image above documents a fold-out picture spread from a rather large, sumptuous coffee table book about “Ancient Egypt”. It was purchased at a discount at a busy estate sale, which I guess means a third-party business managed a garage sale at a gigantic home.

I remembered this picture spread when I read the two passages below from Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. Reading them made me think about how photography, especially my earliest childhood encounters and consumption of pictures of the art and artifacts of “Ancient Egypt” and other civilizations, provided so much of the literal and figurative framings and frameworks for understanding the past. And later popular movies. The picture above, of a modestly sized space and the rough stacking of items, is nowhere near how movies like The Mummy have reimagined the vast, treasured halls of a Pharaoh’s just-broken-into-and-about-to-be-ransacked tomb, or something.

“The murder of five thousand Egyptians who struggled against Napoleon’s invasion of their sacred places and the looting of old treasures, which were to be “salvaged” and displayed in Napoleon’s new museum in Paris, is just one example of this. In the imperial histories of new technologies of visualization, both the resistance and the murder of these people are nonexistent, while the depictions of Egypt’s looted treasures, which were rendered in almost photographic detail, establish a benchmark, indicating what photography came to improve. ”

“My proposition, however, is that photography did not initiate a new world; yet, it was built upon and benefitted from imperial looting, divisions, and rights that were operative in the colonization of the world in which photography was assigned the role of documenting, recording, or contemplating what-is-already-there. In order to acknowledge that photography’s origins are in 1492, we have to unlearn the expertise and knowledge that call upon us to account for photography as having its own origins, histories, practices, or futures, and to explore it as part of the imperial world in which we, as scholars, photographers, or curators, operate.”

This particular experience and deployment of photography is not unique, it’s commonplace, and continues to enact and reproduce ideas of desire, sympathy, consensus, and extraction, croping out so much of the terror, power, and violence exercised upon others and their capacities for self-determination.

Azoulay’s article, published in 2018, was in service of her eventual book, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, which was published in 2019.