Two articles addressing the historical complexities and psychological compromises of Asian American life in the United States

“Being Asian American has always been a bewildering and complicated experience. You move to a new country and think you’ll be treated like an American, but what you really want is to be treated like you’re white, which isn’t possible.

There is a common Chinese saying of 吃苦 (chīkǔ). It translates literally to “eat bitterness,” to swallow our pain and suffering and endure it. We persevere and we don’t complain, and it is seen as a virtue: Work hard for things that people can’t take away from you. In a study of ethnically diverse cancer patients, they found that Asian Americans reported the lowest pain scores. My mom would not have seen the terrifying incident with our old neighbor as something to tell us about. Sharing it would have meant she was complaining. He used words. He didn’t cause her physical harm. He didn’t even use a racial slur. So, maybe it really wasn’t that bad.

...

The damaging model-minority myth suggests that Asians actually have it pretty good in this country, especially compared to everyone else, and propels a perception of universal success (in reality, Asians have the largest income gap with one of the highest poverty rates). It also implies that with higher education and hard work, you can chīkǔ racism. I’ve been shamefully ambiguous as to how prejudiced white America is to Asian Americans, giving white supremacy the “benefit of the doubt” it did not deserve. I’ve been constantly made to feel like I should be grateful for what I have, but what I really have is an uneasy, panicky feeling that I should have spoken up for more and sooner.”

via The Cut

“And here we come to the heart of the complexity of “speaking up” for Asian-Americans. Thanks to the “Model Minority” myth — popularized in 1966 by the sociologist William Petersen and later used as a direct counterpoint to the “welfare queen” stereotype applied to Black Americans — Asian-Americans have long been used by mainstream white culture to shame and drive a wedge against other minority groups.

...

These past few weeks, it seems as if Americans have opened to a kind of knowing. As I saw these recent incidents of anti-Asian violence unfold in the news, I felt a profound sense of grief. But I also experienced something akin to relief. Maybe, I thought, now people will start to respond to anti-Asian violence with the same urgency they apply to other kinds of racism.

But then I started to feel a familiar queasiness in the pit of my stomach. Is this indeed what it takes? A political imagination (or, really, lack thereof) that predicates recognition on the price of visible harm?”

Images and resources I'm working through

“When King Was Dangerous” (Jacobin article for additional labor and class context)

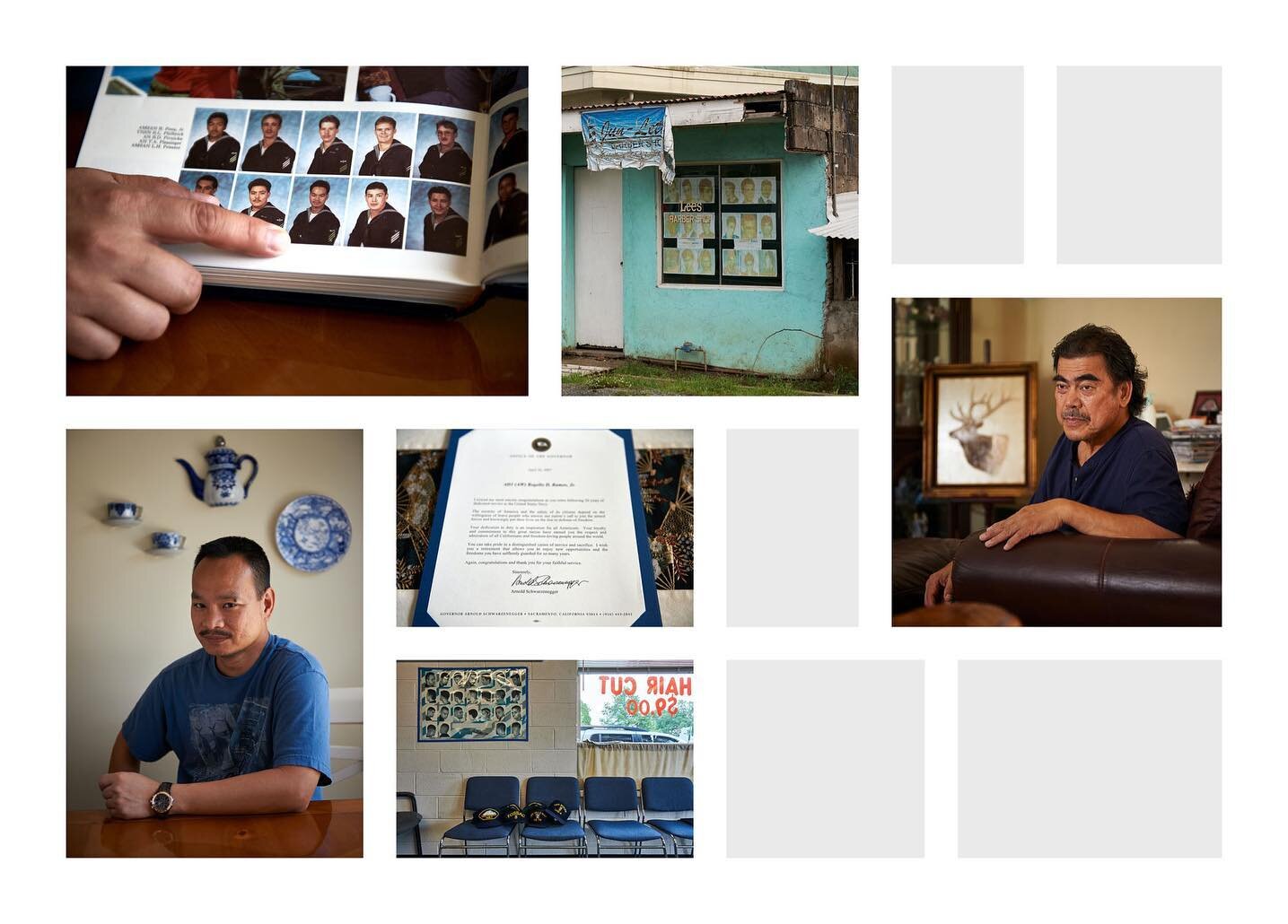

As a Filipino American who is grateful for the life and good fortune I’ve enjoyed in America, I’ve been inspired by others who are challenging themselves, their friends, and their families to take stock of their values and how they choose—every single day—to enact them. Through them and others, I’m beginning to recognizing how my largely silent, passive non-racist attitude/outlook—which I understood as positive, or at least not harmful—has made me complicit in supporting a status quo that continues to damage the lives of Black individuals, families, and communities in this country.

Since high school I’ve always held in high esteem the idea I first learned from reading Emerson: that personal reform is social reform. I still draw strength and inspiration from that conviction, which is why I’m showing these images and linking to these resources. But it is frighteningly clear that such a romantic commitment—so heavily weighted towards the poetic burden of transformative private acts by the individual—can be both indulgent and self satisfying. It is also not social reform. Rather, I’m drawn today to the more direct and still poetic idea attributed to Dr. Cornel West, one that’s finding new life and meaning on and off the Internet:

“Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public.”

Finding common cause in collective action and standing alongside others is how laws and systems of oppression are changed. That’s the direct—and public—path to protecting and supporting Black lives.

It should be summer Olympic time, but it’s not. This now powerful and iconic image (of a peaceful protest that was reviled at the time, and for some time afterwards) taken by John Dominis is absolutely and firmly about the courage and achievement of American gold and bronze medalist sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Mexico games in 1967. But because the subject of this post is about committing to help, I’d like to share a link to the story about Peter Norman, the Australian silver medalist sprinter who stood with them on the podium. From the article:

“Smith and Carlos had already decided to make a statement on the podium. They were to wear black gloves. But Carlos left his at the Olympic village. It was Norman who suggested they should wear one each on alternate hands. Yet Norman had no means of making a protest of his own. So he asked a member of the U.S. rowing team for his “Olympic Project for Human Rights” badge, so that he could show solidarity.”

If you continue to read the article, you will learn that Peter Norman was shunned publicly and largely forgotten for this act of solidarity upon his return to Australia.

So here are some resources and googledocs I am reading and working through as an individual. They were shared to me by others, and offered with the hope that individual listening, learning, and working for change can be a transformative social good.